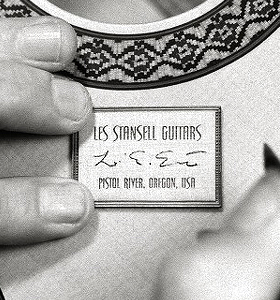

LES STANSELL’S ALTERNATIVE SHELLAC FINISH FOR GUITARS

PRE-RAMBLE:

Looking at Les Stansell’s Youtube video on his alternative shellac method of finishing begs for one of those open-mouth responses like ”shazam” because it does seem like magic. You want to know every detail and every nuance. Of course, Les has obviously been freely giving of information concerning lessons he has learned and you could always call or E-mail him but chances are in the midst of the finishing project, you are going to have more questions or need to make some judgments that may or may not work out.

What I would like to do with this article is to attempt to clarify some of the details behind the procedures as well as giving you a printed version of the step by step process for your reference to keep you from running back and forth between your computer and your workshop.

This all started because I wanted to do something for Les for helping us neophytes with our finishing woes. I am very respectful of any relationship I have with professional luthiers. Most need to be paid for offering advice and probably all should be. So, I write this article to give Les a break from answering the same questions over and over in return for his much needed help. I have never met Les since I live on the opposite side of the US but I admire his work greatly.

Most of us spend a lot of time getting an instrument ready to finish. And we have bought various books and videos on French polishing. Alternatively, we cannot justify $300 to $500 for spray equipment plus the cost of creating a spray booth acceptable to your wife. My workshop is in my basement and I already get a lot of chin music from the misses regarding dust. So, you try French polishing! It’s supposed to be the finish that has the least interference with the sound production. My French polishing looks fantastic until I spirit off the oil coming to the surface. Afterwards I have never been satisfied. After trying that little routine for 5 guitars, I started looking for something else.

Before we begin, I urge you to watch the video several times and stop it at varying points so you can absorb what’s going on. I must have watched it 20 times and I seem to pick up something different every time. Think about where you have problems and see how Les deals with them. His approach may not work for all of us but if we are having problems with the finish at the neck joint or on the top near the fretboard we need to consider how we are going to deal with these issues.

Finally, I want to emphasize that I am in no way an expert on this method. On my 4th and 5th guitar after I had completed the French polishing process, I begin with the micromesh process (step 11 below) and then followed with the polish. So my approach took about two weeks longer than it should have. Also, I had issues with clouding that I traced back (I think) to not spiriting off the oil completely. Therefore, I would recommend that initially you stay as close as possible to Les’s method. Also, I want to tell you that after spending a few minutes on the phone with him, it is clear that his method is evolving and he doesn’t hesitate to try different approaches so don’t be afraid to experiment to find what works for you.

THE PROCESS:

If you have the instrument completely ready to finish you are really already behind the eight ball. Les completely finishes the necks heel joint and the portion of the side wood near that which drops into the slots prior to assembly so make a note for your next build and give this a try. If you didn’t do this, I recommend you use a fad with a beveled eraser inside for this joint (See Youtube French polishing with Michael Thames). That’s the best alternative solution I have found.

The first two steps deal with getting the instrument ready to finish. There are numerous articles that go into depth on this subject. Some helpful articles I have read are on the Milburn Guitars website, in the Cupiano and Bogdanovich books as well as informative articles on both the LMI and Stewmac websites. If you don’t get these first two steps right, no finishing method will help you except maybe 30 coats of lacquer.

- Begin by using the hand scraper and chisel where appropriate and then sanding the entire guitar smooth with 220 grit sandpaper. Les uses both a scraper and chisel often. The scraper is particularly valuable in areas like the binding edges and around the rosette and head stock where sandpaper does not work well or could spill colored dust into the surrounding light colored wood pores. The chisel is also used often in sharp corners where the scraper cannot go or on the head stock where you are dealing with end grain.

- Rub the guitar with Naphtha and check closely for gaps, glue residue, dents, etc. Make repairs as necessary.

- Brush on a heavy (“Flood”) coat of shellac.

This is the “foundation” for the finish. This is not one coat but many coats. What you are doing is basically saturating the wood until it cannot accept any more shellac. In Les’s own words, he is literally pouring the shellac on very quickly until it begins to pool. He will give the instrument a little time between coats to allow the shellac to penetrate into the pores and be absorbed until the wood can accept no more. This could be 5 or 6 coats. At some point the brush will just be pushing the shellac around and begin to remove shellac instead of laying down more. You should be able to see and feel this happening.

At this point in the video the fretboard was not on the guitar but the next picture shows the fretboard glued on. Les told me sometimes he will tape off the area underneath the fretboard position and other times he will scrape back the overlap so as not to compromise the fretboard gluing process. However, you want to make sure you get a heavy buildup of shellac on the top just next to the fretboard position.

The video shows a dark amber shellac confirmed by Mr. Stansell because he prefers the color. However, when I used Amber or darker shellac, my cedar top became blotchy. I thought that maybe Port Orford cedar accepts it OK. What Les told me was the way to stop blotchiness is to get the flood coat on “quickly” before lines begin to form. I suggested using an initial sealer coat with super blond flakes. Les said that doing this first will prevent you from adding color by using a darker shellac later so if you want to darken the wood in the final finish you must begin with that color. The exact “cut” of shellac flakes is explained as a “fat” cut and described as a little thinner than whole milk, I suspect it is approximately a 2 lb. cut.

- Removing the initial flood coats

After the flood coats are applied, the instrument is scraped, sanded and chiseled, ALL the way back to the wood with 220 sandpaper (finer grit size paper does not allow for needed traction). So why do it? Well, as we know the difference between “porous” wood and “non-porous” wood is the size of the pores because all wood in porous. We just don’t need special pore filling substance for certain woods. However, the flood coat will penetrate the wood through the small pore openings or any unfilled pores after the pore filling process. So I suppose you do not have to go all the way back on say Rosewood if you know you have 100% coverage with your pore filler.

By the way, on these heavy flood coats, watch shellac running down the side from the top or back because not all of us are as neat as Mr. Stansell. You’ll have a lot of extra sanding if you forget to check and wipe off the excess before it dries. Also, you cannot scrape the top because the wood is too soft. The top must be sanded.

- Subsequent heavy coats

Next, you begin the heavy coating process again on the top, back, sides, neck and headplate. These coats (maybe 3 or 4) are added 2 days apart. Again, you are saturating the wood. Being a bit more careful with these coats this time will save some sanding time. Plus, this time you are going to level and not entirely remove these layers of the shellac finish. In order to do the sides, the guitar can be put into a vise with soft jaws so as not to flatten the fretwires as you see in the video. These coats are again put on quickly with a brush or other suitable pad.

- When dry, a scraper is used on the sides, back, neck and head to level the heavy coats of shellac. Also at this time the binding is given a 45 degree bevel. In the video, it does not look as though he worried about getting this perfect before he moved on to step 7.

- The guitar is then sanded with 220 sandpaper backed with a sanding pad. All Les’s sanding is done with the foam pad from the micromesh set. It is sanded quite well but not all the way back to the wood. As stated above, this is a more serious leveling procedure. In this procedure the top, neck and headplate are also sanded with 220 paper. Close up of the headplate from the video shows shellac clearly remains but the finish has been thoroughly leveled. The guitar is then wiped off with a clean cloth.

- Base finishing coats

The guitar is allowed to rest for 2 days while the shellac is allowed to dry and harden. Mr. Stansell next puts on nitrile gloves and applies a new coat with a pad. He uses straight strokes only and recharges often but he takes more pains to get a more even coat this time through. This step is to the top, back, sides, neck and headplate. The shellac remains thick. He holds the guitar to do the sides rather than using the vice. Some overlapping has to take place in this step. You will see no gaps in the coverage. At this point, the bridge has not been glued on so he will have to later position the bridge and remove the shellac underneath. It is an important supplement to your finishing knowledge to watch Les’s video on bridge making also on his Youtube channel. In addition, he has taped off the neck to cover the sides and does the reverse to do the neck area around the heel. Remember, very little work is required in this area because it was completely finished prior to assembly so this is only touch up work.

There is a little more to this process than any video could show. Every other day, Les adds 2 or 3 coats one half hour apart. One the idle days, he sands or levels the previous days coats. So, the bottom line is 15 to 20 coats are added followed by a leveling procedure again using 220 sandpaper.

- Rest time

Then the Guitar is set aside in an environmentally controlled room for 2 weeks (longer if you are not in a rush) to allow the shellac to rest and harden. The longer you rest it before you complete the polish step the harder the shellac will get and the better your initial finish will be. I just hang mine in the closet of a spare bedroom with jury rigged hanger. Our central heating and air unit with a humidifier works well for me.

- Bridge Area

When you are ready to begin the micro-mesh and polishing process, begin with the top around where the bridge will ultimately go. Start with the 1,500 and go all the way through 12,000 including the Novus polish. Then locate the bridge position, mask it off and glue it in place. Les uses two guide pins drilled into the top through the saddle area. If you place the bridge on before you do this sanding and polish step, you will never get this area cleanly polished. The next picture in the video shows the top with the bridge glued on and the top looks like the shellac looks finished. Les’s professionalism is beginning to appear. See point 5:39 in the video. Also, it does not appear that there was any glue residue around the bridge area so he’s super neat or he has a way of getting that off without ruining the shellac finish. Actually, Les told me you must have “squeeze-out” or you do not have enough glue for the bridge. The masking tape will take most of this “squeeze-out.” He uses a chisel for the remaining “squeeze-out” and a brush lightly dampened with water for any final residue. Again see his bridge making video.

- Micro-mesh sanding process for the remainder of the instrument

Mr. Stansell then again begins the other parts of the instrument with 1,500 grit and goes all the way through 12,000 grit sanding lightly with each grit. As he goes higher in the grit process, he is polishing the guitar by removing larger scratches and introducing smaller scratches until with the 12,000 grit the scratches left cannot be seen by the naked eye. The video shows this process only on the top but he performs the same procedure on the back and sides.

- Final Polishing

Finally, the guitar is polished by hand with Novus #2 fine water based scratch removing polish. He made it clear this is not a wax. It is a mild abrasive that lessens the scratches left from the 12,000 grit. And because the Novus abrasive is in a slurry, it gives a more even disbursement of the abrasive particles. The video does not show that a great deal of polishing is necessary. The polish says to keep rubbing in a circular fashion until the polish is dry. You should plan on a little more polishing time than the impression given by the video. Also, I would not expect to see Stansell-like results the first time. My first attempt at this left something to be desired. For now obvious reasons, no matter how hard I worked, I could not get the areas around the bridge and near the fretboard to look as neat as other areas. Next time I’ll be better informed and prepared.

Another important point Les wanted me to add was that this finish will craze in a few months. It will show up as haze but when you look at it with your close up visor, you will see tiny cracks occurring in the finish. He also told me that every French polished guitar he had examined has also had this problem. However, with this finish, you start with the 1800 micromesh and go through the 12,000 again and then re-polish with the Novus and the finish will be permanent and will not craze again. Les does not suggest your customer start taking the micromesh sandpaper to their instruments unless they have wood working experience. Often, he will give some of the Novus polish to his customer so they can maintain an acceptable finish using only the polish. While at first this looks like a drawback, my experience has been that even nitrocellulose lacquered guitars craze. But with Les’s method, the finish does not have to be reapplied. In fact, Les told me that no shellac is added on this refinishing process. If you do, it will melt all the shellac layers below and create other problems.

As you can see, this is not a short and sweet finishing process. That’s not what Les was looking for. It is a different way of getting an attractive finish that would offer some protection for the instrument and not adversely affect the sound. For me, I can look forward to getting my next guitar to the finishing stage and embrace the finishing process instead of dreading it. I hope this little write up will be helpful to you. If it is, take time to offer up a thank you to Les for sharing his knowledge with us. And, if anyone compliments you on your finish be sure to share the credit with the man who developed the process. Good Luck!!!